Former LVAD patient Kyree Miller holds an Abbott HeartMate 3 at our DeviceTalks Boston show in May. [Photo by Jeff Pinette for Medical Design & Outsourcing/DeviceTalks]

Kyree Miller, a 30-year-old college student, navigated seven long years of heart failure with the assistance of an Abbott HeartMate left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

“Before I got my LVAD, there was no way I was getting on a plane. Before I got my LVAD, there was no way I was going back to work. And I was able to do both of those things — and more. To be at Killington [ski resort] with an LVAD, I never thought it would have happened, but it did,” Miller told a group of medtech insiders during our annual DeviceTalks Boston show in May.

In August 2022, Miller received a new heart.

“Having the LVAD was crucial in bridging the gap before the heart transplant,” he said. “Without it, I don’t think I would have been here to receive the transplant.”

Miller was fortunate to live in Boston, a city that’s one of the nation’s top healthcare and research hubs. He was near top-notch hospitals with access to LVADS such as Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Massachusetts General Hospital. Cardiologists at top hospitals knew what LVADs could do.

“Being here with the big centers a stone’s throw away was a big help,” Miller said.

His story highlights a challenge that Abbott officials are fighting to answer.

An Abbott marketing illustration shows an implanted HeartMate 3 LVAD with its external equipment. [Image courtesy of Abbott]

The company’s research has shown that its HeartMate 3 pump can extend the lives of advanced heart patients by at least five years. However, Abbott estimates the U.S. has 15,000 advanced heart failure patients who are managed with inotropic therapies alone; they have a projected median lifespan under a year.

“Kyree is lucky to be in a place where he can get access, was referred, and had people who made the right referral based upon the disease that he had. And the benefits are obvious,” said Dr. Robert Higgins, president of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and EVP of Mass General Brigham.

“The challenge that we’re thinking about is that not everyone has a cardiologist, or access to advanced heart failure therapies,” Higgins continued. “And in particular, [minorities] and women don’t necessarily have access to advanced heart failure therapies, which include LVADs, as well as the modern technologies — transplant being one of them.”

Miller later said: “As a gay black man, the healthcare system can’t be one-size-fits-all, either. And in some ways, it feels like it is.”

LVADs can save the lives of people with heart failure

The HeartMate 3 pump [Image courtesy of Abbott]

Implanted through open heart surgery, a left ventricular assist device pumps blood from the lower chambers of the heart to the rest of the body. It can provide a crucial bridge to keep someone like Miller alive until a donor heart is available for transplant. Even when a person isn’t eligible for a transplant, it can sometimes still provide years of extra life.

The transformative power of LVADs in the realm of advanced heart failure therapy cannot be overstated. Abbott’s HeartMate devices became the sole LVAD technology available in the U.S. when Medtronic stopped sales of its HVAD in June 2021 due to mounting issues with the platform.

Abbott’s latest generation HeartMate 3 is smaller than a baseball. Its Full MagLev Flow Technology utilizes a fully magnetically levitated, self-centering rotor that does not require hydrodynamic or mechanical bearings. The result, according to the company, is gentle blood handling to minimize complications and hemocompatibility-related adverse events.

There are over 50,000 patients who have been implanted with Abbott’s HeartMate II or HeartMate 3, and at least 1,000 of those who received the HeartMate II have lived for over 10 years with LVAD support, according Dr. Robert Kormos, division VP of global medical affairs for Abbott’s heart failure tech.

Abbott has some ideas about how to help

Even a multibillion-dollar company such as Abbott can’t reform the U.S. healthcare system’s care disparity on its own, but company officials think there are things they can do to improve the situation.

They’re working on smaller pumps. And Kevin Bourque — VP of R&D at Abbott — thinks better education could clear up a misunderstanding among some doctors that a HeartMate 3 won’t fit in smaller patients, including women and children.

A recent study found it’s the size of the heart that matters more than the size of the patient, he said.

“A couple of years ago, we got a pediatric approval for our HeartMate 3 devices that are being put into children as young as 7 or 8 years old,” Bourque said. … “There certainly is some room to go to get into truly small patients, truly small chests. But that’s not the whole trick, being smaller. I think we need to be physiologically responsive as well. So we’re thinking about how do we make these devices not just be life-savers, but life-optimizers. With all of those strategies in play, I think we can start to reduce the bridge, approaching the value that transplant can bring. We’re kind of on the precipice of doing that.”

In general, better education and dissemination of heart failure treatment guidelines among physicians would help, according to Higgins.

“I think education is going to be critically important to help physicians understand not only that there are at-risk populations, women and persons of color, but everybody benefits from an informed provider who can identify heart failure at its earliest stages and get patients into a comprehensive therapy,” Higgins said.

Kormos suspects the medical community may be too focused on treating symptoms but neglecting the underlying cause. “The problem with that is that by the time a patient says, ‘I don’t feel good anymore,’ it’s too late.”

Access to better cardiac diagnostics and monitoring could catch heart problems earlier so people have time to find out about LVADs as an option.

“We have a pulmonary pressure monitor that we put in people, the CardioMEMS, which is a small dime-size sensor that goes into the pulmonary artery and can measure changes in your pulmonary pressure. We know that with heart failure, that goes up, and as it goes up, your right heart starts to fail,” Kormos said.

According to recent studies, CardioMEMS can nearly halve heart failure hospitalizations and significantly reduce the risk of death.

Miller still has a CardioMEMS inside him.

“I don’t necessarily use it, obviously, as much as I used to,” he said. “But every once in a while just to do a check in, we still actually use it just to make sure that things are going in the right direction.”

If Miller hadn’t gotten into a cutting-edge hospital system he wouldn’t have had access to CardioMEMS or an LVAD — and he wouldn’t be around today, Higgins said. “People are dying waiting for that type of technology.”

Kormos said Abbott and other major medtech companies have been working on more inclusive clinical trials and designing devices to serve more diverse populations.

All of Abbott’s efforts matter because LVADs not only keep people alive, Bourque said, but they enable them to lead productive lives.

Said Bourque: “Every year that Kyree lives is a valuable thing. You’ve returned to society.”

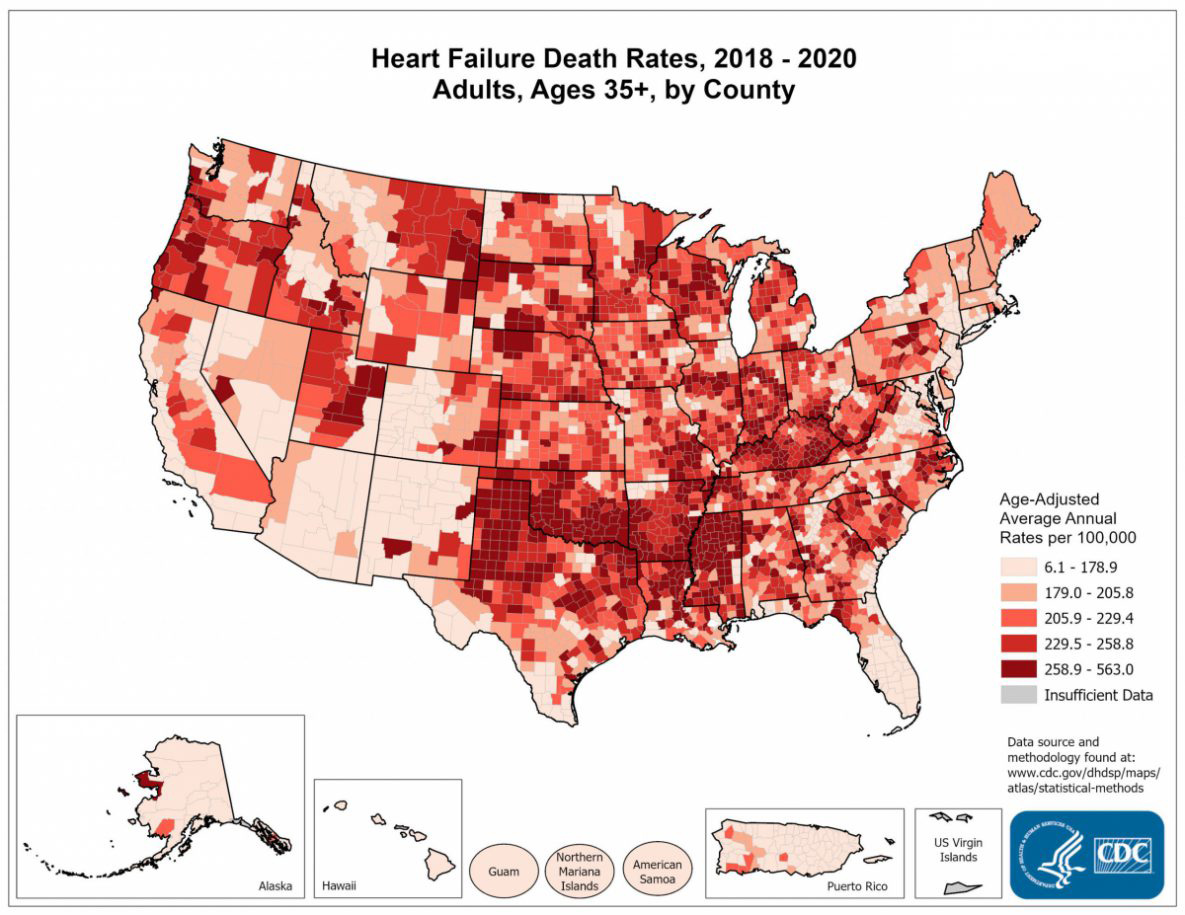

A map from the CDC’s website illustrates the disparity of heart failure outcomes in the United States. [Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]