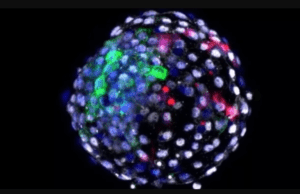

In this monkey-human embryo, human cells glow in red. [Image courtesy of Weizhi Ji / Kunming University of Science and Technology]

A group of scientists from the U.S. and China injected human stem cells into 132 macaque embryos, which then developed for up to 20 days.

While the research holds promise for organ transplants, studying disease and testing new drugs, it also prompts controversy.

The research was published this month in Cell.

The scientists began with blastocysts from macaques. They injected 25 human extended pluripotent stem cells into each of those cells, which replicate in the embryos’ tissue.

Researchers have previously injected human stem cells into organisms ranging from rodents to cattle to nonhuman primates to create chimeras. Previous research includes mice with human immune systems for AIDS research and rats with human tumors.

But the growth of human stem cells in macaque embryos was more extensive than in previous research involving animals such as pigs, triggering alarm from ethicists. For instance, a human-pig chimera developed in 2017 had 0.001% human cells.

The recent research could foretell future chimeras with substantially higher percentages of human genes.

Scientists currently lack the means to control how human stem cells act in a monkey embryo, leading to the possibility that scientists in the future could engineer a monkey with human genetic material in the brain.

Indeed, researchers at the University of Rochester engineered laboratory mice with human cells. One year after transplanting human fetal brain cells into the laboratory mice, they learned the cells had taken hold in the mouse brains. The engineered mice were generally more intelligent than unmodified animals, excelling in memory and cognition tests.

While primate research is often difficult in the West, China has prioritized creating primate disease models since 2011 to research neurological diseases.

Chimeras that incorporate human genetic material into other primates could potentially lead to better models of diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, which often pose challenges for drug developers.