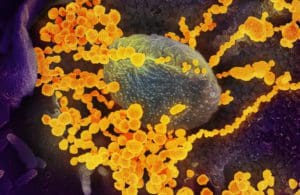

SARS-CoV-2 electron microscope image from Wikipedia

Highly-transmissible COVID-19 variants have likely been circulating undetected for months in places like the U.K., South Africa and Brazil. They then seemed to burst onto the scene, fueling large outbreaks that dwarfed preceding ones.

While the variants aren’t well understood, they suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is mutating in ways that confer an evolutionary advantage. They thus threaten to become dominant throughout much of the world in coming months unless protocols such as growing vaccination, mask-wearing and social distancing can slow their spread.

The new variants are also likely to change the fight against COVID-19 in crucial ways. Here are four facts to consider:

1. New variants could delay herd immunity and make vaccinating children more important

After FDA authorized mRNA vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna in late 2020, it seemed that herd immunity was plausible in 2021. The consulting firm McKinsey estimated that the U.S. would hit that threshold in the third or fourth quarter. While McKinsey still stands by that projection, the firm acknowledges that the slow initial rate of vaccination and the rise of more-transmissible variants could delay herd immunity.

If emerging viral variants are more transmissible and diminish vaccine efficacy, achieving herd immunity will require more people to get vaccinated than previously assumed. McKinsey now estimates that 65% to 80% of the population would need to have vaccinated immunity. That works out to 78% to 95% of individuals over 12 years old.

Vaccinating many children could help lead to herd immunity, especially as new strains could be more transmissible in children. But there are little data on COVID-19 vaccines on children and adolescents. However, the Pfizer-BioNTech is authorized for ages 16 and higher, and the company is studying the vaccine in patients as young as 12 years old.

Another question is the extent that new variants can confer natural immunity. Early evidence from Manaus, Brazil, suggests that the B.1.1.248 variant circulating there poses a higher risk of reinfection than the virus’s parental lineage.

2. New variants could further elevate the status of mRNA vaccines

One of the most powerful tools in battling COVID-19 in the long-run could be mRNA vaccines, which can be customized to optimize efficacy against emerging variants. mRNA vaccines support “a ‘plug-and-play strategy,’” said Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, a research fellow at the National Institutes of Health.

Early evidence suggests that vaccine candidates from Johnson & Johnson (NYSE:JNJ) and Novavax (NSDQ:NVAX) have a measurable drop in efficacy against the South Africa variant B.1.351.

Moderna is already testing a custom version of their mRNA vaccine, mRNA-1273.35, designed to be more effective against the South Africa variant and lineages with similar mutations.

BioNTech CEO Uğur Şahin has said that its current vaccine should be effective against currently circulating variants. Still, it said it could develop a new version in six weeks if needed.

3. The Brazilian and South Africa variants could redraw battle lines in the pandemic fight

A growing amount of data suggests that the South Africa variant N501Y.V2 will reduce vaccine efficacy. Phase 3 results from Johnson & Johnson (NYSE:JNJ) found the single-dose vaccine was 72% effective in the U.S. but only 57% effective in South Africa, where 95% of cases involved the N501Y.V2 variant.

Phase 3 data from Novavax (NSDQ:NVAX) indicated that the company’s vaccine was almost 90% effective in the U.K. but 60% effective in a Phase 2b trial in South Africa, where roughly 90% of cases involved the N501Y.V2 variant.

The South African and Brazilian variants feature a greater number of mutations related to the virus’s receptor-binding domain on its spike than the U.K. variant, which has a single mutation (N501Y). Data from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna suggest their vaccines can competently neutralize viruses with the N501Y mutation. Clinical evidence indicates that the two vaccines are less effective against the South Africa variant.

While the Brazil variant P.1 features similar mutations compared to N501Y.V2, there are little data pitting vaccines against the virus.

However, researchers believe that P.1 has helped fuel a massive resurgence of COVID-19 infections in January in Manaus, Brazil. Much of the population there had already been infected in the spring of 2020.

It is also possible that the variant from Brazil is more dangerous as the company recorded 1,710 deaths per million inhabitants likely attributed to COVID-19 infection, which is considerably higher than the mortality rate in the U.K, U.S. and elsewhere, according to the publication Science.

The P.1 variant has at least two mutations that reduce antibody effectiveness. But while the P.1 and N501Y.V2 variants may be less sensitive to neutralizing antibodies, they are unlikely to “cause widespread vaccine failure,” wrote Dr. Paul Offit in JAMA.

4. Delaying second vaccine doses could fuel further viral mutations

A handful of countries, such as the U.K., have approved delaying administering second doses of two-dose vaccines by up to 12 weeks to prioritize giving the prime vaccination to as many people as possible.

The impact of that strategy is unclear. One potential outcome, however, is that it drives further SARS-CoV-2 mutations that escape human antibodies. Such escape mutations tend to occur when a virus confronts a host who has developed some degree of immunity but cannot stop viral replication completely.

“The scenario of virus evolution in the face of suboptimal immunity is one reason extending the interval between the first and second dose of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine might be problematic,” wrote vaccinologist Dr. Paul Offit recently in JAMA.