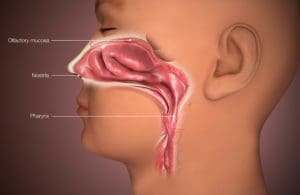

Mucosa and relevant structures. [Image from Wikipedia]

The COVID-19 vaccine landscape is gradually becoming more diverse. And it could grow more so, as several companies work on intranasal vaccines.

Intranasal vaccines offer potential advantages over traditional intramuscular vaccines. They can stimulate immunoglobulin A production, which can avert infection, as a recent Scientific American article noted.

“It’s not insignificant to go from a needle-based delivery to nasal delivery,” said Dr. C. Buddy Creech, who is the director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program.

Buddy Creech, MD. Photo by Joe Howell

The approach has several clear advantages. Intranasal vaccines would likely generate mucosal immunity, reducing the virus’s odds to take root in the respiratory tract.

And once pediatric COVID-19 vaccines are available, the intranasal route could be well-tolerated in younger children who are needle-averse. “Having different routes of administration can sometimes be advantageous when you’re trying to use multiple vaccines at once,” Creech said.

Intranasal vaccines could also facilitate vaccination in developing countries.

In any case, having a variety of vaccines available could hasten mass-vaccination. “It is not the time to sit back and relish in our successes of the vaccines that have been developed so far,” Creech said. “We have to continue pushing.”

A year after the World Health Organization classified COVID-19 as a pandemic, it remains vital to “put maximal immunologic pressure on the virus,” Creech said. “If we don’t, then we will start to see variants emerge that do a good job of avoiding our immunity, whether that’s from a vaccine or from natural disease.”

Vaccine developers are involved in an arms race as viral variants continue to emerge. “We need to continue to explore new vaccines, to continue to invest in new technologies that might afford us more protection against these variants,” Creech said.

Drug Discovery: What precedent is there for intranasal vaccines offering superior protection over intramuscular vaccines?

Creech: In the mid-2000s, the Fujian influenza strain emerged. It was a complete mismatch with our guess that we had for the flu vaccine that year. But we found out that individuals who had gotten the intranasal flu vaccine had some protection against that new strain that we hadn’t anticipated — even though it’s made out of the same virus as the injected vaccine.

That’s a really important lesson as we think about coronaviruses. It stands to reason that a mucosally administered vaccine might offer more protection against these drifted strains before they can take hold.

The FluMist flu vaccine is the biggest example of that. The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that set recommendations for using vaccines preferentially recommended the intranasal FluMist vaccine because of its ability to generate such a good immune response.

Not only do we have a precedent of using FluMist in kids, but we also have a precedent of it potentially working better.

The recommendation to use did get withdrawn for a couple of years, but now it’s back.

School-based vaccination can be easier when it’s an intranasal vaccine versus an injected vaccine.

And it makes sense to try to generate immunity in the nose if a virus enters the body through the nose.

Drug Discovery: Could you foresee the public self-administering vaccines one day?

Creech: I think this is going to be the wave of the future. Investigators at Emory have created a little patch that looks like a stamp, but it’s even smaller. But it has these little micro-needles on it that you could apply to the skin and deliver the vaccine that way.

There are novel methods where we could rapidly send out vaccines to people. It’s still the stuff of science fiction. Of course, the challenge will be that it is difficult to get an idea of how many people use the vaccine so we can track things like side effect profiles and compliance, and we can know when people are due for a booster.

The skillset needed to administer an intranasal vaccine is slightly different than what is required for an intramuscular injection. You might open up the number of people who can provide that type of vaccination.

When you’re thinking about mass-vaccination, school-based or workplace-based campaigns, you could see intranasal vaccines being a lot easier to pull off. And it just hurts less.

Drug Discovery: Can intranasal vaccines cause people to test positive for the virus they protect against?

Creech: The one or two times that I’ve received FluMist — the live intranasal vaccine for flu — it causes a pretty good runny nose and a good sore throat.

Depending on the type of product that you use and how it’s made, it could temporarily cause you to be positive.

Many of our COVID-19 tests look for portions of that spike protein. If you squirt a vaccine at the nose that has that spike protein in it, and then you go and get a COVID test, your COVID test might be positive. There could be some operational issues around that.

One intranasal vaccine might be different enough than what we would be looking for in a COVID test so that it doesn’t cross-react. Others might not share that same characteristic. There’s some nuance there.