Smithers’ horseshoe bat is a relative of the bat that likely gave rise to the pandemic. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

When a virus jumps from one host to another, it usually acquires new capabilities to target cells beforehand.

But the SARS-CoV-2 virus seems to have needed little prior adaptation before causing a pandemic, according to a recent study in PLOS Biology.

The genus betacoronavirus to which SARS-CoV-2 belongs is notorious for its threat of jumping from animals to humans. Indeed, the genus is responsible for several outbreaks in the past two decades, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and, more recently, COVID-19.

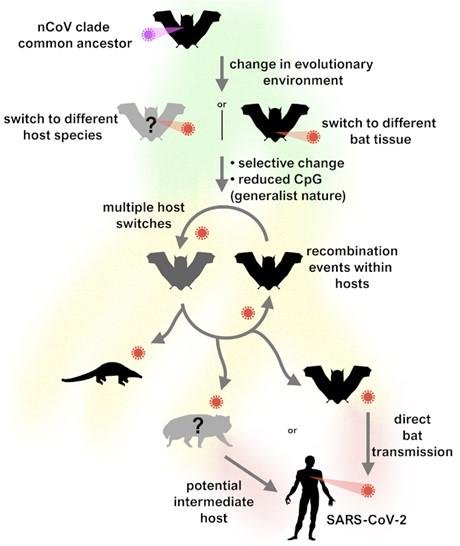

The PLOS Biology study concluded that the nearest viral ancestor to SARS-CoV-2 is RmYN02, which evolved in bats. The ancestor virus of SARS-CoV-2 was likely a “relatively generalist virus” that was capable of efficient human-to-human transmission. It is still possible that an intermediate species spread SARS-CoV-2 to humans.

The main difference between the virus behind the earlier SARS outbreak and SARS-CoV-2 is the latter’s increased ability to cleave to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2), allowing it to infect cells in humans’ upper respiratory tract, albeit with lower disease severity. Paradoxically, however, this capability leads to a more significant disease burden, given the greater case counts linked to SARS-CoV-2 than SARS-CoV, which is now also called SARS-CoV-1.

Schematic of our proposed evolutionary history of the nCoV clade and putative events leading to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

Image courtesy of:

MacLean OA, et al. (2021), Natural selection in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in bats created a generalist virus and highly capable human pathogen. PLoS Biol 19(3): e3001115. CC-BY

Despite the attention recently given to SARS-CoV-2 variants, the virus has not meaningfully evolved after it began infecting humans roughly a year ago based on the hundreds of thousands of sequenced virus genomes.

“This does not mean no changes have occurred, mutations of no evolutionary significance accumulate and ‘surf’ along the millions of transmission events, like they do in all viruses,” said Dr. Oscar MacLean, who coauthored the PLOS Biology study. While mutations affecting the virus spike improve transmissibility, “‘neutral’ evolutionary processes have dominated,” according to MacLean.