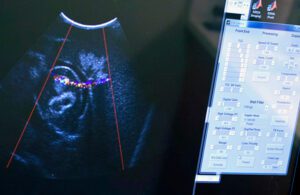

A new kidney stone treatment uses ultrasound to move and break up renal calculi without sedation. [Photo courtesy of University of Washington]

A new kidney stone treatment uses ultrasound to reposition and break up renal calculi in patients with minimal pain, no surgery and no anesthesia.

University of Washington researchers are using ultrasound propulsion to move kidney stones for easier passage from the kidney through the ureter to the bladder. They also have burst wave lithotripsy to break them into smaller pieces.

Doctors often advise kidney stone patients to let the stones pass naturally, a process that can mean weeks of intermittent, intense pain.

Even then, some stones are too large to pass. Health providers then turn to extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy to break them up. It’s a painful procedure that requires sedation and can cause damage to the kidney.

It’s also possible to snare or break up smaller kidney stones with a ureteroscope inserted through the urethra and bladder to the ureter. Larger stones may require removal with a surgical procedure called percutaneous nephrolithotomy through an incision in the back.

The new ultrasound approach, by comparison, is “nearly painless, and you can do it while the patient is awake and without sedation, which is critical,” UW Medicine emergency medicine Dr. M. Kennedy Hall said in a news release.

RELATED: Researchers find roller coasters may help small kidney stones pass

Hall is the lead author of a new feasibility study on the new kidney stone treatment published in The Journal of Urology.

Kidney stone treatment started with spaceflight concerns

The University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory developed this prototype for a new kidney stone treatment. [Photo courtesy of University of Washington]

Development of the new kidney stone treatment started five years ago with a NASA-funded study to see if kidney stones could be treated without anesthesia on trips to Mars and other long space flights.

“We now have a potential solution for that problem,” Hall said. NASA has downgraded kidney stones as a key concern as a result of the research.

Hall’s study had 29 patients: 16 treated with propulsion alone and 13 with propulsion and burst wave lithotripsy. Physicians used handheld transducers on the skin to send ultrasound waves toward the kidney stones, using the waves to shift the stones for a smoother journey to the bladder, or to break them up into smaller pieces that would pass easier.

The treatment moved the stones in 19 patients, including two cases where the stones moved out of the ureter and into the bladder. One patient reported immediate relief when the stone was dislodged from the ureter.

In seven of the patients, burst wave lithotripsy fragmented the stones. Two weeks after the treatment, 18 of 21 patients with stones lower in their ureter closer to the bladder had passed them. In this group, the average time for passage was about four days.

The next step is a clinical trial with a control group to evaluate the technology.

New kidney stone treatment in emergency rooms

More than half a million people visit emergency rooms with kidney stones each year, according to the National Kidney Foundation. The organization estimates that about 10 percent of people will have a stone at some point in their life.

The researchers hope their new kidney stone procedure could be used to move or break up kidney stones with ultrasound in clinics or emergency rooms.

Their study already treated patients at UW Medicine’s Harborview Medical Center in Seattle and University of Washington Medical Center emergency departments.