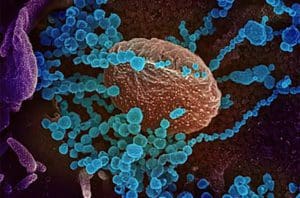

This colorized scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (round blue objects), the virus that causes COVID-19, emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. [Image courtesy of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases]

The idea of inhalable COVID-19 vaccines may not be new, but, until recently, no country had approved a COVID-19 vaccine with an alternative delivery route.

That changed on March 31, 2022, when Russia greenlit the Galaleya Institute’s Sputnik V inhaled vaccine. The country authorized a similar nasal-drop-based vaccine known as Salnavac on July 4, 2022.

To authorize those vaccines, Russian regulators weighed data from the formerly approved Sputnik V vaccine in conjunction with Phase 1/2 safety and immunogenicity data from the intranasal versions of that vaccine.

More recently, China authorized the inhalable Convidecia Air COVID-19 vaccine from CanSino Biotech.

India followed suit on September 6 by authorizing BBV154 from Bharat Biotech.

Several drug developers are currently conducting clinical trials in countries ranging from the U.S. to Japan for additional intranasal COVID-19 vaccines.

Inhalable vaccines have found some traction in the U.S., albeit for flu rather than COVID-19. On February 29, 2012, FDA approved FluMist Quadrivalent. That vaccine was indicated for individuals between the ages of 2 and 49.

Although the FluMist vaccine historically fared well in children, the vaccine hasn’t fared as well in adults. According to a Nature article, the difference in efficacy between children and adults may have to do with adults’ cumulative immunity to flu, which may interfere with the attenuated vaccine’s ability to work as intended.

Intranasal COVID-19 vaccines could generate mucosal immunity, reducing infection and transmission rates.

“As the current set of intramuscular COVID-19 vaccines reduce the likelihood of severe infection but do not block transmission, and vaccinated individuals can pass on infection while asymptomatic, there remains a high risk of being stuck in a cycle of ‘waves’ of infection—despite high primary and booster vaccination rates—as we try to emerge from the pandemic,” said Janet Beal, senior research analyst in health economics and market access at GlobalData.

Prior inhaled and oral vaccines for other pathogens and allergens have proven successful at generating mucosal immunity.

If inhalable COVID-19 vaccines can do the same, “they could effectively block COVID-19 viral entry across the mucosa and subsequent transmission, representing a step-change in our global emergence from the pandemic: a way to break the cycle,” Beal said.

To date, however, there is relatively little clinical evidence for inhalable COVID-19 vaccines. The situation could quickly change, however, if more countries continue to authorize inhaled vaccines.