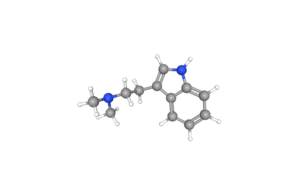

[Image courtesy of PubChem]

Interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics may have exploded in recent years, but the field will likely see “a lot of separating the wheat from the chaff,” said Dr. Rick Strassman, a professor at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and author of “DMT: The Spirit Molecule” and “The Psychedelic Handbook.”

In the 1990s, Strassman conducted pioneering research on the psychedelic DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine), which is found in many plants and animals.

While the number of psychedelic companies has exploded recently, the herd may already be thinning. Several public companies in the space have seen their valuations plummet over the past year.

“I think there’ll be more consolidation,” Strassman predicted. “There will be just a handful of players in the end.”

Strassman recommends that companies and academics interested in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics avoid making unsubstantiated claims or minimizing the adverse effects of the drug class.

The companies that most effectively tap the potential of psychedelics while reducing the risk of adverse events are the most likely to find traction in the marketplace. Several researchers, for instance, are working on developing compounds inspired by drugs such as LSD or psilocybin without causing hallucinations.

“I think this new development of so-called ‘non-psychedelic psychedelics‘ might turn out to be an interesting twist on the whole story,” Strassman said.

In the following interview, Strassman touches on the potential to use DMT in stroke rehabilitation and psychotherapy while noting the risks accompanying psychedelics. This conversation has been lightly edited.

Could you share more on your collaboration with psychedelic companies?

Rick Strassman [Image courtesy of rickstrassman.com]

Strassman: That started about two years ago once the big interest started developing in pharma for applying psychedelic drugs to various clinical conditions. I consulted with a lot of groups for about 18 months or so. And it has significantly quieted down the last maybe six months or so. I’m conversing with about three groups now. Some of these companies formerly interested in psychedelics had no idea what they were dealing with. They had no IP, and they burned through their cash in no time at all.

What is your take on the potential of DMT in stroke patients?

Strassman: So far, so good. It’s quite impressive with respect to the animal data. I think the first order of business will be to perfect the infusion protocol over six hours. And then start doing some careful, incremental work with patients.

What about Algernon’s planned Phase 1 study, which involves a prolonged IV infusion of DMT to stroke patients?

Strassman: It’s a very small, sub-psychedelic dose. In our studies in the 1990s, there was a fairly complete dose-response study of DMT in a group of normal volunteers. The smaller, sub-psychedelic doses didn’t affect blood pressure and heart rate. So you’re spared the mind-blowing and cardiovascular effects with small doses.

The infusion will be continuous because that seems to be most beneficial in terms of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis as compared to one single bolus.

How novel is it to give prolonged IV infusions of DMT?

Strassman: Most psychedelics lead to tolerance and cross-tolerance to each other.

In the early 1990s at the University of New Mexico, we discovered we could repeatedly dose DMT without inducing tolerance. I received funding for an NIH study to see if we could induce tolerance to DMT. It was unique because it didn’t induce tolerance to closely spaced dosing.

In our research, we gave one dose of DMT every half hour, four times in the morning. And there was no tolerance to the psychological effects. God only knows why that’s the case. I don’t think anybody’s looking at that, to be honest.

But the fact that we couldn’t induce tolerance led me to suggest a continuous infusion toward the end of my DMT book, “The Spirit Molecule.”

Andrew Gallimore — a colleague in Japan — and I published a theoretical paper on a continuous infusion and how you would do it. The group at Imperial College just published a poster on a continuous infusion of a fully psychedelic dose for over a half hour. So you can do it in humans, and Algernon will extend that model.

What do you think of using a continuous infusion of DMT in conjunction with psychotherapy?

Strassman: You could develop a very interesting psychotherapy model with a continuous infusion of DMT.

Once you swallow your psilocybin or LSD, the patient has an experience for multiple hours. And you can’t bring people down.

If you’re infusing DMT, you can turn up the infusion rate or you can lower the infusion rate. You can stop the infusion rate. The subjective effects will follow suit within a few minutes.

If you know somebody is working on things with their therapist, they may want to go deeper for half an hour or 15 minutes and then come out of the process. So I think it will perhaps generate an interesting psychotherapeutic paradigm once the infrastructure and logistics are worked out with the infusion model.

I’m currently collaborating with a group at UCLA that’s interested in using repeated dosing of DMT in veterans with PTSD. The whole idea is that you give a big dose, and you process. And you go back, and you have your trip, and you process over several hours.

I also think with a continuous infusion, you’ll be able to characterize the subjective effect of DMT more carefully than is now the case with just a half hour or 15 minutes of experience.

There’s been a debate since the 1960s about whether DMT is significant to mammalian physiology. What are your thoughts on that?

Strassman: DMT is a compound that has been identified in the brain of mammals in quite high concentrations, comparable to serotonin and dopamine. The hunt is on to confirm whether it might be a neurotransmitter, which would be extremely interesting. You’d have to wonder what the function of a DMT neurotransmitter system would be. Concentrations increase in the brain during death in experimentally induced cardiac arrest in rodents, especially in the visual cortex.

DMT is also neuroprotective in vitro in conditions of ischemia, so it could have some safety mechanism whose activity is called into action during times of brain damage or ischemia.

A paper from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, demonstrated colocalization of the two requisite enzymes in the rodent brain and quite high DMT concentrations in the visual cortex. The concentrations increased significantly during death. We still don’t understand what regulates the synthesis of DMT in normal conditions or what the function could be.

DMT may maintain concentrations of BDNF and regulate Sigma-1 sites. It’s extremely interesting. If there were a DMT neurotransmitter system, it would stimulate the same receptors in the brain that psychedelics stimulate. So it might play a role in everyday perception, mood, consciousness and those factors.

You can go down some rabbit holes when thinking about endogenous DMT. Back in the day, there was an interest in naturally occurring DMT vis-à-vis psychosis, especially schizophrenia. You could speculate that overproduction of DMT, perhaps, is involved in schizophrenia. And if it is, you could somehow blockade its effects or modify its metabolism. That might prove to be an effective antipsychotic.

To the extent that non-drug states resemble those brought on by giving DMT, it makes sense that your naturally occurring DMT may play a role.

The concentrations of DMT in the blood are very, very low. So we can’t quite measure them accurately. Either we will need to look at metabolites or activation of the genes or the enzymes or other ways of indirectly measuring the activity of DMT. One of the people who co-wrote the article from Ann Arbor a few years back is now at UC San Diego. His postdoc, Jon Dean, is interested in visualizing DMT in the living human brain using spectroscopy studies.

The hunt is on for what is stimulating or regulating the activity of endogenous DMT.

Do you still think that DMT is an underlooked compound?

Strassman: I do. And I don’t think it’s because of any fault of its own.

Psilocybin has become popular partly because of the winds of past political decisions and the focus on psilocybin from the Hopkins group because of their interest in the mystical experience. Psilocybin doesn’t carry the same kind of baggage as LSD does.

But there were studies of compounds like DMT in the 1950s and 1960s. One compound was diethyltryptamine (DET), and the other was dipropyltryptamine (DPT). They were investigated for alcoholism and end-of-life despair. They demonstrated some encouraging preliminary results.

DMT is a bit difficult to use because of its need to be injected and the short duration of action. But that being said, DMT appears to have therapeutic effects. The duration may not be as important as combining it with your psychological therapy.

A study that came out of Yale a few months ago gave a big dose of IV DMT without any psychotherapy to treatment-resistant depressives, and they improved strikingly as well.

Whether you need to add therapy or not — and if you do, what kind of therapy — is still an open question.

Could you comment on the association of classic psychedelics with cardiovascular side effects?

Strassman: Psychedelic studies tend to be quite small and involve only infrequent dosing. There are field data out there involving people in the Amazon who have been drinking Ayahuasca one, two or three times per week for decades. I haven’t come across any reports of valvular problems in those people.

The studies I co-authored with Dr. Paulo Cesar Ribeiro Barbosa in Brazil mostly focused on psychological and health status. They were field studies and demographic studies. They incorporated questionnaire data as opposed to cardiovascular diagnostic data.

How do you foresee mainstream psychiatry’s view of psychedelics evolving?

Strassman: Psychedelics were a central focus of psychiatry in the 1960s. Once the Controlled Substances Act passed, clinical studies with psychedelics — including DMT — ended.

The Europeans, especially the Germans, are interested in looking at DMT as a psychotomimetic.

What is your view of how regulators’ attitudes towards psychedelics have changed over the decades?

Strassman: I’m not sure to tell you the truth. I stopped my work on DMT in 1995. And then just in practice psychiatry for the next 13 years, just prescribing and doing psychotherapy in private practice and community mental health. I wrote a few books.

It seems to me that we need to be careful. The studies of psilocybin for depression and other things are quite small. And the adverse effects are not trivial. There have been acute suicidal ideations, psychosis and those kinds of things.

So I don’t see the floodgates opening anytime soon.

There have been calls to put psychedelics into Schedule IV. I think that is completely irresponsible. That would involve putting LSD into the same schedule as Valium. It makes no sense and is potentially dangerous. Even if the FDA grants approval, you still need to contend with the DEA, and they are much more hard-nosed when it comes to limiting access.

The more people who trip, the more problems occur at the public health level.

People in the field nowadays are taking smaller doses than back in the 1960s and early 1970s. There’s more traditional wisdom out there talking people down.

But still, many people out there believe psychedelics are cure-alls without many adverse effects. Or they might call them challenging experiences as opposed to adverse impacts. There are going to be accidents and suicides. Another Charles Manson could crawl out of the swamp. It behooves academics and pharma to keep the lid on their unbridled enthusiasm.

So far, there have been no major Pied Pipers for psychedelics. There haven’t been any new Tim Leary or Ram Dass types. In the 1960s, we saw people like that standing in front of thousands of people, calling for the overthrow of the government.

So far, the Pied Pipers — to the extent they are around — are taking a muted approach. Michael Pollan, for example, and Decriminalize Nature are low-key. Their agendas don’t involve the overthrow of the universe. It may be a matter of time, but I think we do need to keep in mind the swinging of the pendulum.

Do you see the growing interest in ketamine for depression as laying the groundwork for more interest in DMT?

Strassman: Yes, I do. Very much. It’s getting one foot in the door of having an intensive short-acting psychedelic experience.

What’s your opinion on the role of integration in psychedelic therapy?

Strassman: The whole integration issue will be key with these companies pursuing psychedelics. The integration therapists I speak to are just picking up the pieces of these poor folks who were hallucinating three days later. They haven’t slept. They’re suicidal.

Integration is going to be increasingly important. That’s especially the case with these people who spend a week or two in the Amazon with ayahuasca coming out of their ears, and then they go back to Chicago. So I think that will be an increasingly important area to suss out.

Interest is also growing in 5-MeO-DMT as a potential therapeutic psychedelic. What do you make of that?

Strassman: There’s some interest in 5-MeO-DMT as an antidepressant. But I think what is going to limit its use is the incidence of flashbacks. They’re prevalent even in normal volunteers with experience smoking 5-methoxy DMT. A Dutch study followed participants in a 5-methoxy DMT retreat where they either smoked it or injected it intramuscularly. The ones who smoked it had a 69% incidence of flashbacks. Can you imagine nearly 70% of depressives having flashbacks when you send them home? It’s a bad idea. I don’t hear those kinds of stories with respect to DMT. 5-MeO-DMT has a reputation as the new kid in town, and everybody wants to study it. Some people say it has great potential for depression, but what about the incidence of flashbacks?