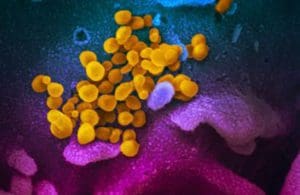

A scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (yellow). Credit: NIAID-RML

Our industry’s response to COVID-19 defied the conventional wisdom that it takes years to deliver new drugs.

Makers of monoclonal antibodies led the pack, most notably Regeneron (NSDQ:REGN), which manufactured the 8-g, two-antibody cocktail administered to then-President Donald Trump last fall. Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY) and Vir Biotechnology (NSDQ:VIR) pulled off similar feats. Prior speed records were measured in years, not months.

Vaccine developers moved even larger mountains. The colossal trials required to assess efficacy and safety — 30,000 to 60,000 volunteers each — were planned, executed and submitted to the FDA in under a year. Most thought it couldn’t be done in under a decade.

And small-molecule drug makers made important contributions too. Despite all the controversy surrounding the red herrings hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, very real progress has been made repurposing previously developed drugs remdesivir, dexamethasone and (perhaps) fluvoxamine.

Looking closer

And yet, we still have a problem on our hands, exacerbated by the contagious Delta variant. Now that we’ve bought ourselves some breathing room, it’s worth asking why all the clever science and unlimited cash have still failed to keep the ICUs and morgues clear of COVID. Looking closer at the successes above reveals plenty of room for improvement.

Injected biologic drugs. Start with injected biologic drugs, represented here by monoclonal antibodies. Manufacturing cost is typically estimated at around $200 per gram, equal to $1,600 in cost of goods sold (COGS) for the 8-gram dose administered to former president Trump. Added to this are significant costs of cold-chain distribution and IV clinic administration. More daunting, this estimate doesn’t include recovery of development costs, said to be over $500 million (albeit 80% covered by taxpayers). The common themes across all varieties of these drugs are costly manufacturing, cumbersome distribution/administration and complex, expensive preclinical development (particularly in cell-line and final-process development).

Vaccines. Dosed in much smaller quantities, vaccines are intrinsically more scalable. But not perfect. It’s fortunate for the vaccine-makers’ business model (and the rest of us!) that the federal government paid for the lion’s share of those enormous clinical trials, an unavoidable feature of all vaccines regardless of the production technology.

And although the vaccine accomplishment is astonishing, it hasn’t been perfect: not all COVID vaccines have worked for everyone, even the mRNA ones. The biggest incumbents failed entirely. Lavish federal funding hasn’t obviated supply bottlenecks, (despite billions in additional government funding). New variants and the passage of time have begun to erode vaccine efficacy, but the large trials needed to test new ones prevent a nimble response. Even the best can’t hold the fort forever; it looks even worse for those that were less efficacious to begin with. Above all, the triple challenge of non-response by the immunocompromised, vaccine-hesitant and needle-phobic means that vaccines cannot solve the pandemic singlehandedly.

Small-molecule drugs. And it’s no accident that few talk seriously about making de novo small-molecule drugs in time to dent the pandemic. Promiscuous binding and high levels of systemic availability make them inherently riskier to develop than injected monoclonal antibodies. Moreover, working through all the safety checks takes a lot of time, and there’s a high failure rate, so medicinal chemists are unlikely to ever beat Regeneron’s record. It’s simply too dangerous to rush — an intrinsic feature of all small-molecule drugs. If anything, the widespread harm caused by misuse of ivermectin is an illustration of these hazards.

So, these three classic drug-making tools — as powerful as they are — still leave plenty of unmet medical need out in the world.

Where do we go from here?

Fortunately, many other therapeutic modalities are available beyond the big three above, which together still account for nearly all global biopharma revenues. Realizing the full potential of new, audacious ideas doesn’t require new technology — just a new mindset, the willingness to reexamine good ideas with fresh eyes.

Fortunately, the cultural tide seems to be with us, at least for the moment. Look at an example outside our industry: before SpaceX did it, no one predicted that a single, privately-held company would drop the cost of a satellite launch by 95% (by building self-landing rockets of all things). Critically, scientific breakthrough wasn’t the key; rather, it was a cultural sea-change — one that gave talented engineers the freedom to look at old problems with fresh eyes.

This is true for biopharma, too; COVID-19 proved it. Like Elon Musk’s rockets, the drug development triumphs in 2020 weren’t the result of eleventh-hour scientific discovery. They stemmed from the creative application of various lines of research decades in the making. If anything, pre-pandemic drug development timelines were growing, not shrinking; it’s widely known that the industry’s ROI for drug development has been below the cost of capital for at least a decade, mainly because just 7.9% of new drugs entering the clinic reach approval.

What changed overnight was our collective mindset in the face of COVID-19: those delays suddenly became unacceptable, so we refused to accept them.

It seems clear that the space for new technology outcomes has opened up for drug development, too. So, how can we best capitalize on this before the window closes again?

Greater diversity of drug modalities

New drug development modalities beyond the three established ones can improve pandemic preparedness and restore our industry’s productivity.

Each of the classic modalities is a tool, useful for solving discrete classes of problems, but we need more tools. You don’t turn screws with a hammer, after all. We need to attack disease from more than three directions. This approach has worked well for HIV and Hepatitis C, and there’s no reason to think it shouldn’t prove equally powerful against COVID-19 and the long list of other unmet medical needs.

What might this look like? Examples abound. A DARPA-funded approach features a herd of dairy cows genetically-engineered to express fully human antibodies — about as unconventional as landing a rocket on its tail. Completely novel therapeutic modalities are ascendant at companies like Laronde Therapeutics (circularized RNA). Independent research teams at the University of Pittsburgh and Oxford University have shown that delivering antibodies directly to the airways — rather than injecting them — can effectively treat COVID-19 and block transmission in hamsters. And microbiome researchers have been throwing up very interesting research results for years now, with drug developers in various fields not far behind, including next-generation fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) and rationally-designed bacterial consortia. Fecal matter capsules are a novel approach by any measure.

Brian Finrow

Our own efforts here at Lumen Bio (Seattle) tidily illustrate many kinds of useful diversity in action: we deliver our protein therapeutics in an unconventional manner (directly to the site of disease, like the University of Pittsburgh team); we use a nontraditional manufacturing host and we fund our program through a uniquely flexible and rapid federal funding mechanism (the MTEC consortium).

One silver lining of the pandemic has been the sparking of a fresh open-mindedness across not just our industry but also its public sector regulatory and funding partners. At the federal level, this fresh thinking is being channeled into creative, new, faster ways to fund research and review drugs. Capitalizing on this moment to lock in place a broader diversity of drug-making tools beyond the three old standbys will leave us better prepared for the next pandemic.

Brian Finrow is cofounder and CEO of Lumen Bioscience.