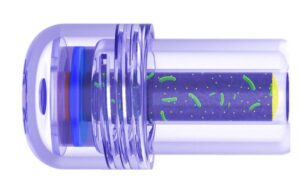

This biobattery could power ingestible cameras in the small intestine. [Image courtesy of Binghamton University]

Researchers at Binghamton University believe they found a solution for powering ingestible cameras in the small intestine.

Professor Seokheun Choi led a team of PhD students. Choi serves as a faculty member in the Dept. of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science. The PhD students include Maryam Rezaie and Zahra Rafiee.

Together, they believe they can power devices in the hard-to-reach small intestine. According to a post on the university website, the small intestine winds around the human gut for an average of 22 feet.

“There are some regions in the small intestine that are not reachable, and that is why ingestible cameras have been developed to solve this issue,” Choi said. “They can do many things, such as imaging and physical sensing, even drug delivery. The problem is power. So far, the electronics are using primary batteries that have a finite energy budget and cannot function for the long term.”

The researchers’ solution builds on Choi’s past findings on utilizing bacteria to create low levels of electricity. This can power sensors and Wi-Fi connections as part of the Internet of Things (IoT). They say other options, like potentially harmful traditional batteries, are less viable. Wireless power transfer from outside the body has inefficiencies, they said, while temperature differences can’t harness thermal energy and intestinal movement is too slow for mechanical energy.

Instead, the biobattery uses microbial fuel cells with spore-forming Bacillus subtilis bacteria. They remain inert until they reach the small intestine, according to Binghamton researchers.

The technology utilizes a pH-sensitive membrane that requires certain conditions to activate. It only works in the small intestine, based on the pH levels, as the stomach has very low pH, Choi said.

While some may not warm to the idea of ingesting bacteria, Choi explained that bodies contain nontoxic microbes that help with digestion and other functions.

“We use these spores as a dormant, storable biocatalyst,” he said. “The spores can be germinated when the nutrients are available, and they can resume vegetative life and generate the power.”

Looking ahead, Choi and the team have improvements to make for the capsule-sized biobattery. For instance, it tends to take up to an hour to germinate completely once it reaches the small intestine. They aim to make that faster.

The cell also generates around 100 microwatts per square centimeter of power density. That represents enough for wireless transition, but the researchers hope to make it 10 times more powerful.

Such batteries would also require animal and human testing, along with biocompatibility studies.

“I believe that our micro-fuel cell has a huge potential, but we have a long way to go,” Choi said.