Dr. Carlos de la Hoz

Physicians, psychotherapists and other health care professionals are collaborating to pioneer strategies to use ketamine to treat mental health disorders, PTSD and chronic pain. One such individual is Dr. Carlos De La Hoz, a triple board-certified anesthesiologist, regenerative medicine and pain-management doctor of the Neomedicine Institute (Doral, Florida).

In recent years, the dissociative anesthetic ketamine has received renewed attention for its potential to treat mood disorders. In small clinical trials, infusions of the drug have led to rapid improvements in mood and reduced suicidality. Ketamine also appears to hold promise for alcohol use disorder.

Prescribing generic ketamine for depression and other mood disorders, however, remains an off-label use of the drug. However, in 2019, Johnson & Johnson (NYSE:JNJ) won FDA approval for Spravato (S-ketamine), a stereoisomer of ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. In addition, Atai Life Sciences (Nasdaq:ATAI) is developing R-ketamine for a similar indication.

Generic ketamine is a racemic mixture of S- and R-ketamine that no longer has patent protection, making it unlikely that a company would perform a Phase 3 study to expand the drug’s label to include treating mood disorders.

The situation has led physicians and professional societies to create ketamine protocols to maximize the therapeutic benefits of ketamine while limiting risk.

In the following interview, De La Hoz shares his experience working with ketamine for depression and other mood disorders and chronic pain, explaining how the molecule can help some patients with seemingly intractable depression and anxiety to improve.

The responses have been lightly edited and condensed.

What is your experience working with ketamine?

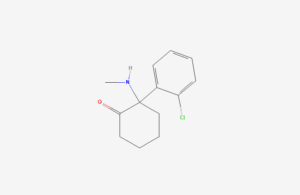

[Image courtesy of PubChem]

De la Hoz: Ketamine is an extraordinary medication or molecule. As an anesthesiologist, I’ve been using it for over 15 years. Since starting training, I have mainly used it as an anesthetic, but I saw the patients had a good experience with it. Using ketamine, we could decrease the amount of opiates and narcotics. In addition, it’s an excellent pain modulator.

We also saw that severely depressed patients had decreased suicidal ideation after receiving ketamine. They start feeling better right away.

Yale helped pioneer the use of ketamine for mental health after publishing a study in 2000 showing significant improvements in depressed patients. That was the first major study.

After that, We started investigating the role of the glutamatergic pathway in depression. Traditional antidepressants focus mainly on serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine. But we started seeing that the glutamatergic pathway can play a significant role in treating depression or anxiety.

In 2019, the esketamine-based nasal spray Spravato got approved, which made ketamine even more mainstream.

There’s been kind of like a rebirth with ketamine. We see a huge link between its dissociative effect and the relief of symptoms that patients experience.

Could you comment on how you use ketamine for depression clinically?

De la Hoz: In the standard protocol, we do an infusion for 40 minutes and make the patients stay for 15 more minutes. After that, they’re more or less back to normal. That’s not the case with psychedelic therapy involving psilocybin or LSD when the effects last several hours or more. Patients need to be supervised and to be guided during treatment.

The IV version of ketamine makes a lot of sense. That’s where we have most of the research. That’s the safest way to deliver it. With IV ketamine, if we see any serious alterations in blood pressure, which is the most common side effect, we can stop the infusion immediately, so we don’t have unnecessary risk. Also, if the patient feels uncomfortable, we can stop the infusion immediately. That usually resolves the issue right away.

Are bladder side effects a concern for the therapeutic use of ketamine for depression and other mood disorders?

De la Hoz: The literature has documented the issue of chronic abuse in recreating settings where the dosages are high.

Most of the time, with therapeutic ketamine, bladder inflammation is transient. Once the patient stops doing ketamine, the symptoms are completely gone. I have not had any patient experience bladder problems from ketamine, but we don’t recommend ketamine for chronic use. And our therapeutic dosages are one-tenth of what is used for anesthesia.

We still have to do a lot of research on the long-term side effects of using ketamine for depression and mental health problems, but so far, the only thing we see is transient increases in blood pressure. And we advise patients with uncontrolled blood pressure or severe heart disease not to undergo the therapy.

How do you think of ketamine as a therapy for depression and other mood disorders?

De la Hoz: The idea is to serve as a bridge or to be a guide to help a patient with a transition.

When ketamine is used with antidepressants, we see that ketamine can shorten the time of action.

There was a study in 2016 where ketamine was used in conjunction with Lexapro (escitalopram) that found a single ketamine infusion significantly accelerated oral antidepressant efficacy.

This is important because we see that when patients are placed on antidepressants in the first few weeks, there’s a higher incidence of suicide. And we need something that can address that. We think that ketamine might be the answer.

We see ketamine as another tool in a toolbox where it can help patients on antidepressants get control of symptoms faster. Or it can be used in conjunction with psychotherapy, where we see the most benefits. Ketamine with psychotherapy can help patients with mood disorders go to the root of the problem where they are accessing the traumas of past experiences. Such experiences can be part of the reason why these patients have depression. In psychotherapy, we can help patients change thought patterns and process maladaptive thoughts.

One of the particular things ketamine does is that it creates a connection between the conscious and the unconscious mind — the frontal cortex and the limbic system. So that puts you in this type of waking-dreaming state where you can access your unconscious. So you can talk about past traumas with more ease and less stress. And that way you’re able to kind of cope with those traumas.

We see patients who have had a lot of trauma — child abuse, neglect, and all these things. Usually, after the first few sessions, they start seeing a change. Patients are more open. They can access their emotions and are more in touch with themselves. They start feeling better. We have patients that have lost productivity, and they gain it back. Alcoholics who can barely leave the house can go days and days without drinking after receiving ketamine.

We see patients who have been dealing with depression for years. We have had a lot of patients with depression since they were adolescents. And now they are in their 20s and 30s and haven’t found a solution. So it’s gratifying when you’re able to help them live a better life.

We’re using ketamine as a tool for patients to heal and find long-term solutions. So the idea is not to put patients on ketamine for a prolonged period of time.

Do patients interested in ketamine for mental health sometimes worry they could become addicted to it?

De la Hoz: Ketamine still has a stigma, given its history as a recreational drug. People abusing it snort whatever dosage they feel is appropriate.

That’s not what we are doing here. Three aspects impact how patients are going to react, feel and respond. The first is dosage, which we control. The next is the setting, which is different from a recreational setting. In a clinical setting, we control all the external input. For example, patients get an eye mask and have music. They are in a controlled environment having an introspective experience. Another element is the patients’ mindset. They usually will have gone through psychotherapy and set an intention for the experience.

All of these factors vastly decrease the chances of abuse. We haven’t seen any patient say, ‘I’m craving ketamine. I want to do it again tomorrow.’

Initially, some patients are concerned about ketamine’s history of recreational use.

After patients finish the protocol, we check how they feel for several weeks afterward. And then, if needed, they’re placed on a maintenance program. Not everybody needs it. We have patients that have completed the original protocol who feel great.

How do you compare ketamine to antidepressants?

De la Hoz: Antidepressants help about one-third of patients. In some cases, patients have a partial response. We want ketamine to be one of those tools that we can access along with psychotherapy, exercise and biofeedback.

Traditional antidepressants are based on the theory that a serotonin imbalance is implicated in depression. Proving that isn’t easy. It has been inconclusive, and unfortunately, we cannot get patients, measure their serotonin levels and see if they are likely to respond to an antidepressant. We need to do a better job of providing patients with alternatives to antidepressants.

What are your thoughts on ketamine accessibility, given that it is not usually covered by insurance?

De la Hoz: The esketamine nasal spray Spravato is covered by insurance. A single treatment session without insurance costs hundreds of dollars.

Ketamine infusions range between about $350 to $700, depending on your location.

Hopefully, insurance companies will cover it once there is more data. But there’s not currently a lot of interest in getting ketamine an FDA indication for depression.

IV ketamine is very good for many reasons. We can titrate the infusion. We know exactly what we are giving. Some companies are sending out ketamine via mail order. We don’t advocate for that. In the future, we can hopefully have other formulations like nasal spray or sublingual forms that decrease the financial burden for the patient that might be covered by insurance in the future.

The incidence of adults taking antidepressants has nearly doubled since the beginning of the pandemic. We need to find alternatives to antidepressants and prevent this epidemic of depression.

What do you see as the main disadvantages of conventional antidepressants?

De la Hoz: Emotional numbing can be a problem. You may experience some relief from your depression, but you can’t enjoy anything, either. We also see decreased libido. And you can go into withdrawal if you stop these medications without tapering them with the proper guidance.

Many patients feel they cannot get off antidepressants even if they want to.

One important thing to know is that antidepressants were not designed to be taken chronically. Yet, we’ve seen patients on antidepressants for decades with an increased incidence of heart disease and stroke.

Antidepressants have their place, but we need to have a plan of what will happen next after a patient starts antidepressants. The longer the patients take antidepressants, the more difficult it is for a physician to get them off. Often when a patient on antidepressants sees a doctor, that physician leaves the patient on the antidepressants.

We don’t have prospective studies to measure the side effects of being on antidepressants for many years. We know that serotonin plays a role in different processes in the body. And most antidepressants are increasing that concentration. We know that most of our serotonin is in our gut system, and antidepressants alter our gut serotonin. We need to do more clinical studies to determine the side effects.

Can you speak to how ketamine for depression induces neuroplasticity?

De la Hoz: We see that ketamine increases the production of a few growth factors in the brain, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Those growth factors increase plasticity and spur connectivity in the brain. In addition, the growth factor increases blood flow. That, in conjunction, creates the possibility for new connections to reshape the brain, causing a reset. Neuroplasticity can enable a shift in maladaptive patterns and thoughts involved in a loop of depression, anxiety and other symptoms.

We have seen patients have an increase in memory after ketamine therapy. They can also develop new ways of dealing with life situations.

We also see maladaptive thoughts in some patients with chronic pain. These recurrent thoughts can trigger more pain and cause depression and anxiety. With neuroplasticity, the brain can reshape itself. When patients go to psychotherapy, they can change their thoughts, which makes it possible for them to make long-lasting changes.